As it had done in World War One, the Bank turned to women at the beginning of the second war to ensure it could maintain banking services on the home front and meet the needs of military personnel overseas in its role as paymaster to the armed services.

A previously exclusive male career, banking had discovered that women offered equally valuable talents when given the opportunity.

The necessities provided by war opened the door to women across the country. But, as the years showed after both world wars, old habits and beliefs took a long time to shrug off, and previous biases re-asserted themselves as soon as the conflicts ended and the men came home from the battlefronts.

That had been the case in 1918 when the proportion of women employed by CBA to fill the gaps caused by male military service rose to 40 per cent of the expanded total staff of 1,415. More than 580 women filled roles such as clerks – once the sole preserve of men.

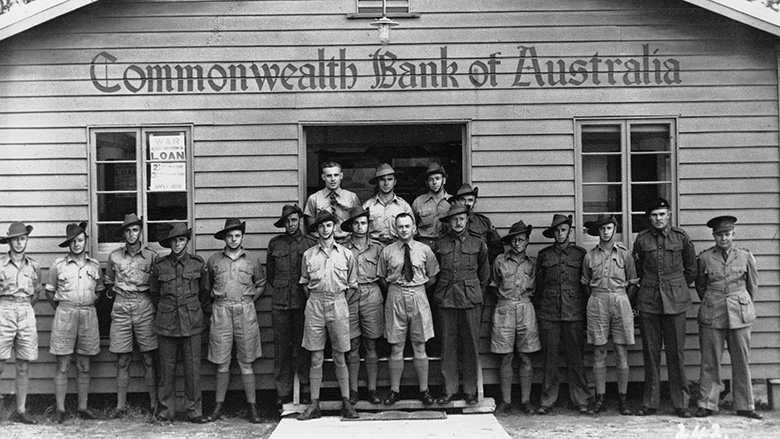

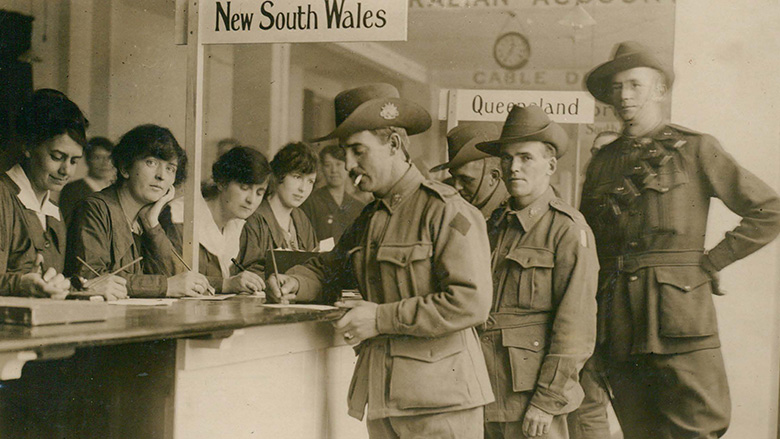

Australian soldiers doing their banking in 1917 (Reserve Bank of Australia Archives; PN-000270)

Australian soldiers doing their banking in 1917 (Reserve Bank of Australia Archives; PN-000270)

Some of them subsequently left the bank as their male counterparts came back from war or as they got married – with the policy at the time forcing women to resign their positions as soon as they entered into marriage.

The number of women working at the bank only grew slowly during the inter-war years, primarily because of the limited job opportunities. By 1939, only 670 women were on the bank’s payroll, even though the organisation had grown in size and by geographic location.

Females represented just 15 per cent of total employment, which at the start of World War Two stood at 4,530.

That again all changed as nearly two-thirds of the male staff enlisted to fight in the war. Many of the women who were taken on to replace them had worked for the bank before - former typists who had been forced to quit because of the public service rules preventing married females from being employed.

The bank also turned to other known quantities to keep the place running. Former staffers – affectionately known as “re-treads” - came out of retirement to fill key positions while school teachers and university students were seconded during holiday periods to help out.

In fact, anyone with a decent education and a head for numbers was a prime candidate for employment.